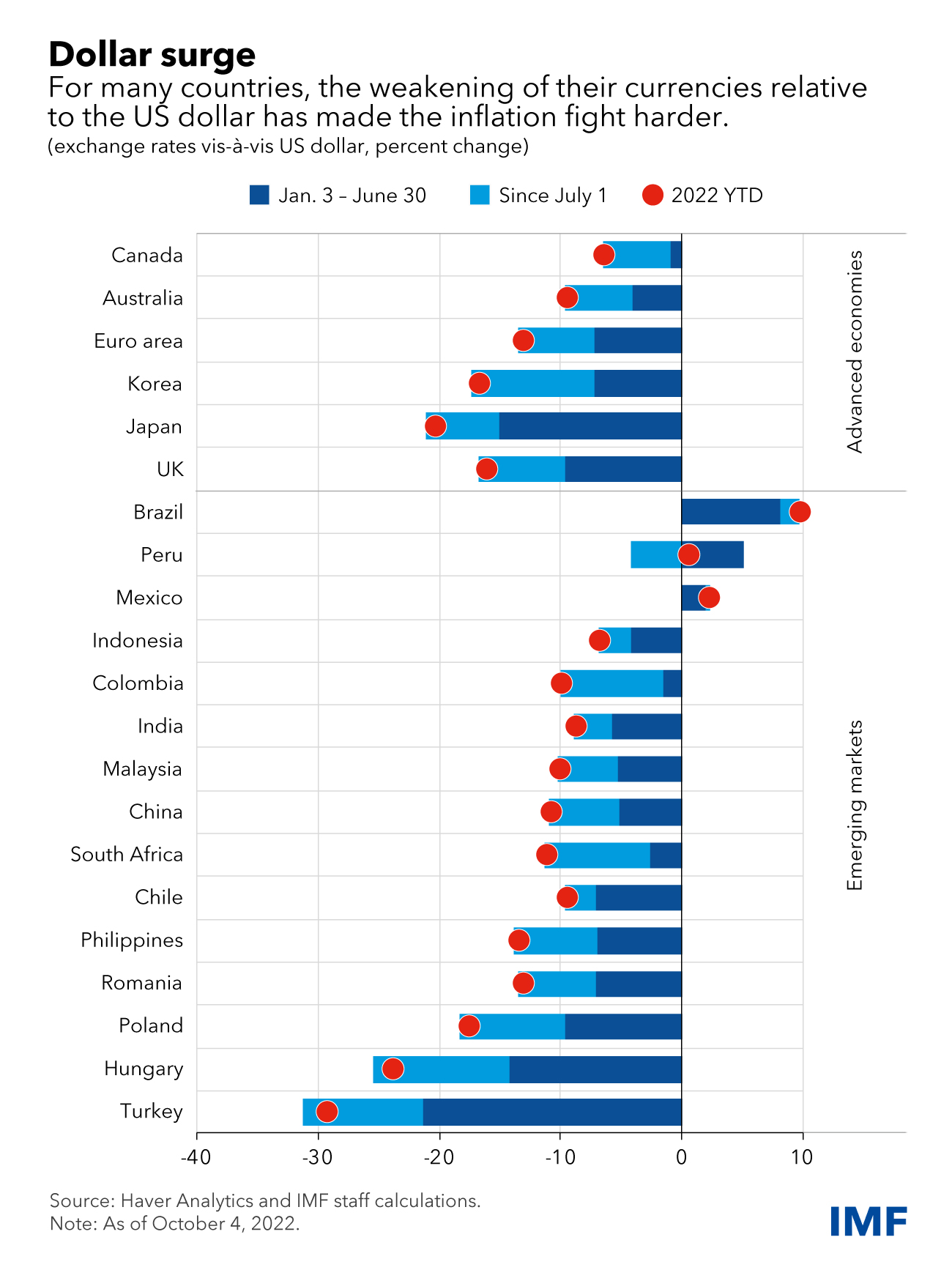

The dollar is at its highest level since 2000, having appreciated 22 percent against the yen, 13 percent against the Euro and 6 percent against emerging market currencies since the start of this year.

Such a sharp strengthening of the dollar in a matter of months has sizable macroeconomic implications for almost all countries, given the dominance of the dollar in international trade and finance.

While the US share in world merchandise exports has declined from 12 percent to 8 percent since 2000, the dollar’s share in world exports has held around 40 percent. For many countries fighting to bring down inflation, the weakening of their currencies relative to the dollar has made the fight harder. On average, the estimated pass-through of a 10 percent dollar appreciation into inflation is 1 percent. Such pressures are especially acute in emerging markets, reflecting their higher import dependency and greater share of dollar-invoiced imports compared with advanced economies.

The dollar’s appreciation also is reverberating through balance sheets around the world. Approximately half of all cross-border loans and international debt securities are denominated in US dollars. While emerging market governments have made progress in issuing debt in their own currency, their private corporate sectors have high levels of dollar-denominated debt. As world interest rates rise, financial conditions have tightened considerably for many countries. A stronger dollar only compounds these pressures, especially for some emerging market and many low-income countries that are already at a high risk of debt distress.

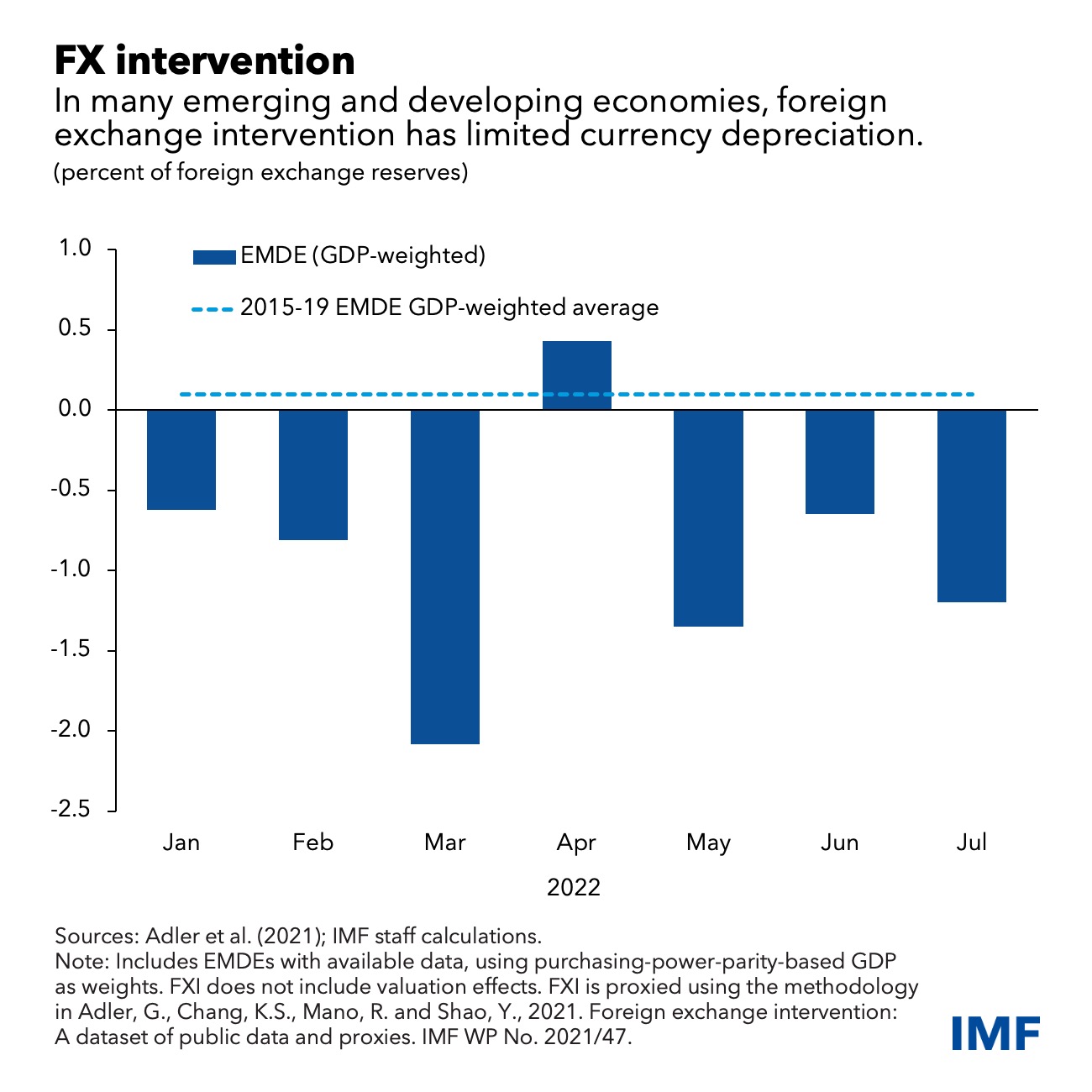

In these circumstances, should countries actively support their currencies? Several countries are resorting to foreign exchange interventions. Total foreign reserves held by emerging market and developing economies fell by more than 6 percent in the first seven months of this year.

The appropriate policy response to depreciation pressures requires a focus on the drivers of the exchange rate change and on signs of market disruptions. Specifically, foreign exchange intervention should not substitute for warranted adjustment to macroeconomic policies. There is a role for intervening on a temporary basis when currency movements substantially raise financial stability risks and/or significantly disrupt the central bank’s ability to maintain price stability.

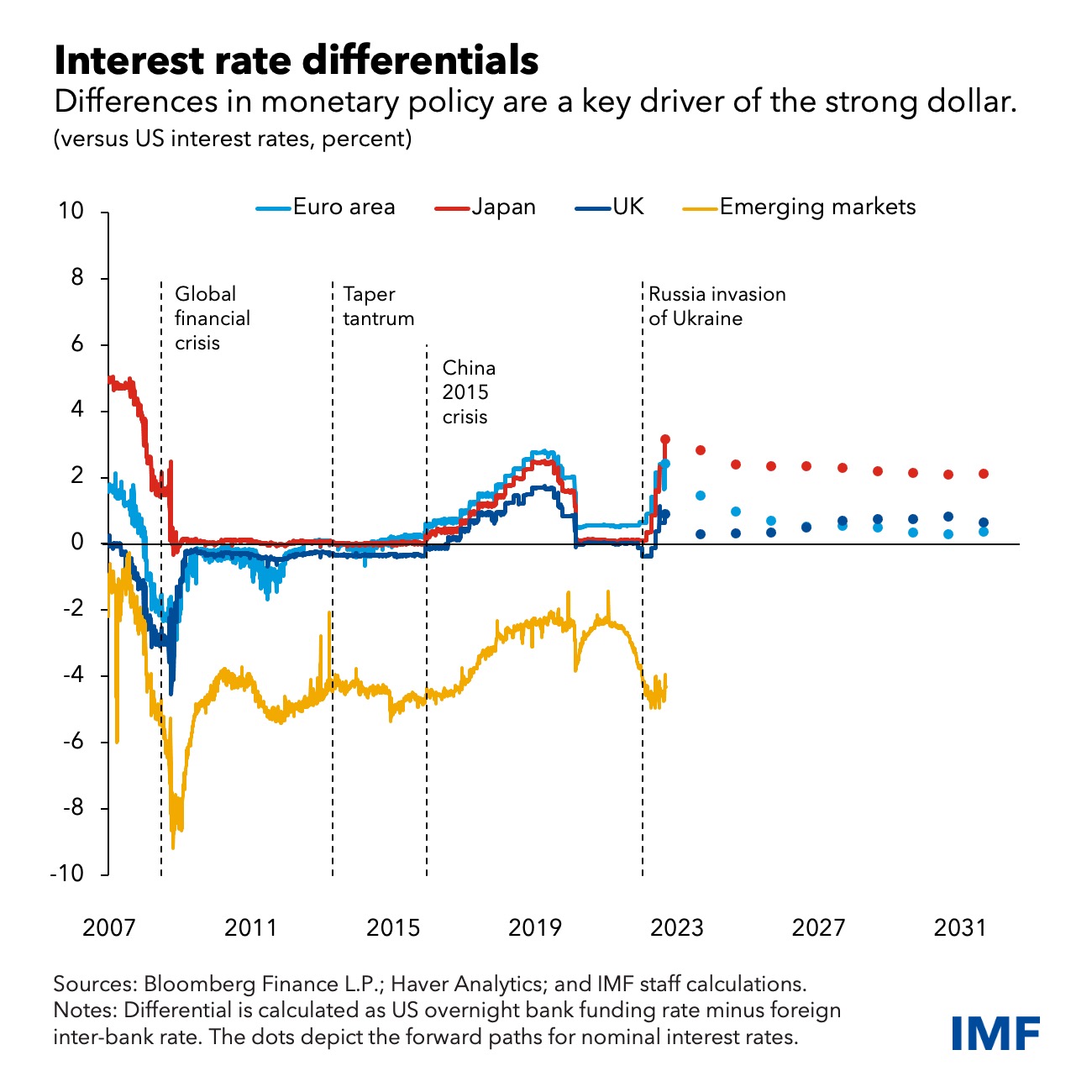

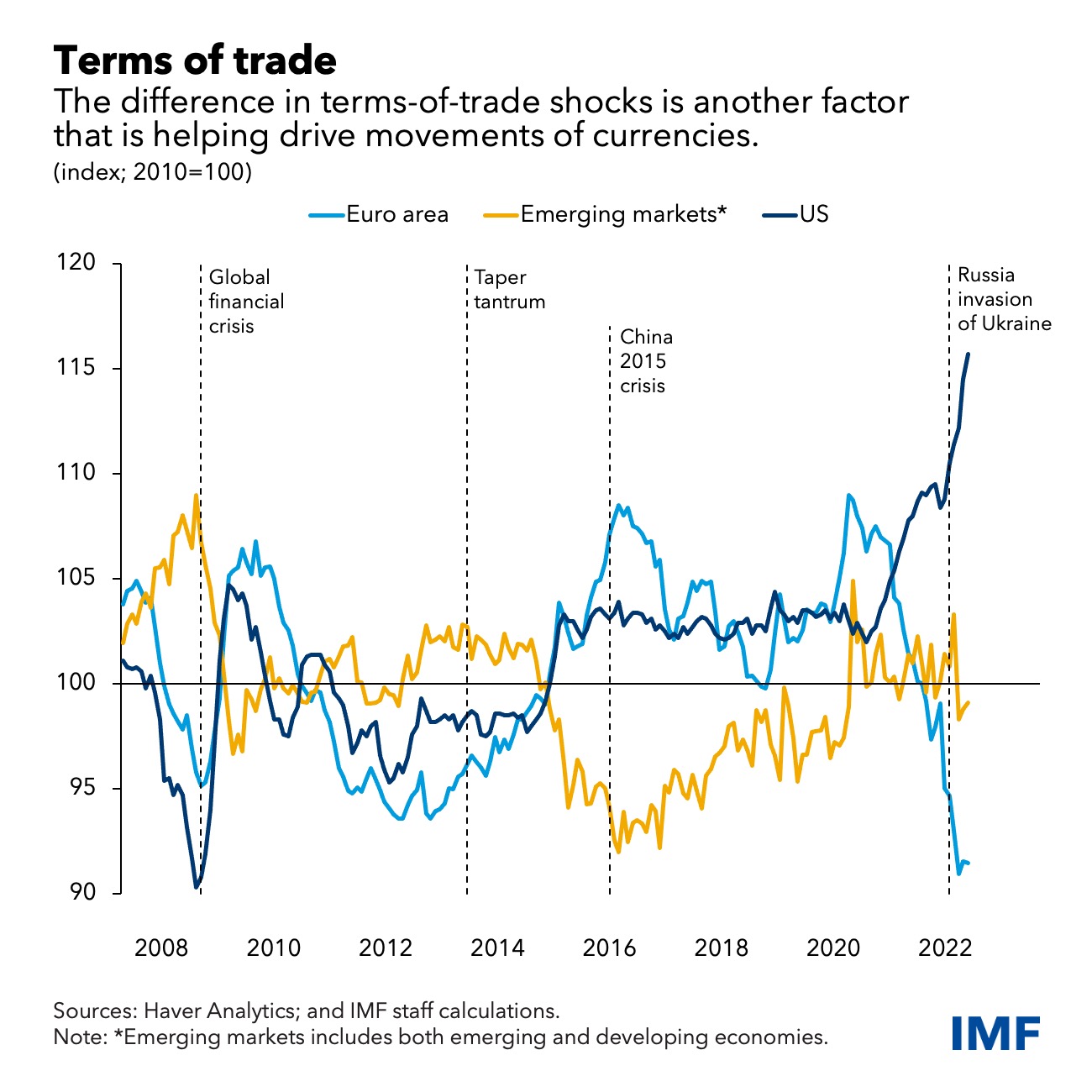

As of now, economic fundamentals are a major factor in the appreciation of the dollar: rapidly rising US interest rates and a more favorable terms-of-trade—a measure of prices for a country’s exports relative to its imports—for the US caused by the energy crisis. Fighting a historic increase in inflation, the Federal Reserve has embarked on a rapid tightening path for policy interest rates. The European Central Bank, while also facing broad-based inflation, has signaled a shallower path for their policy rates, out of concern that the energy crisis will cause an economic downturn. Meanwhile, low inflation in Japan and China has allowed their central banks to buck the global tightening trend.

The massive terms-of-trade shock triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the second major driver behind the dollar’s strength. The euro area is highly reliant on energy imports, in particular natural gas from Russia. The surge in gas prices has brought its terms of trade to the lowest level in the history of the shared currency.

As for emerging markets and developing economies beyond China, many were ahead in the global monetary tightening cycle—perhaps in part out of concern about their dollar exchange rate—while commodity exporting EMDEs experienced a positive terms-of-trade shock. Consequently, exchange-rate pressures for the average emerging market economy have been less severe than for advanced economies, and some, such as Brazil and Mexico, have even appreciated.

Given the significant role of fundamental drivers, the appropriate response is to allow the exchange rate to adjust, while using monetary policy to keep inflation close to its target. The higher price of imported goods will help bring about the necessary adjustment to the fundamental shocks as it reduces imports, which in turn helps with reducing the buildup of external debt. Fiscal policy should be used to support the most vulnerable without jeopardizing inflation goals.

Additional steps are also needed to address several downside risks on the horizon. Importantly, we could see far greater turmoil in financial markets, including a sudden loss of appetite for emerging market assets that prompts large capital outflows, as investors retreat to safe assets.

Enhance resilience

In this fragile environment, it is prudent to enhance resilience. Although emerging market central banks have stockpiled dollar reserves in recent years, reflecting lessons learned from earlier crises, these buffers are limited and should be used prudently.

Countries must preserve vital foreign reserves to deal with potentially worse outflows and turmoil in the future. Those that are able should reinstate swap lines with advanced-economy central banks. Countries with sound economic policies in need of addressing moderate vulnerabilities should proactively avail themselves of the IMF’s precautionary lines to meet future liquidity needs. Those with large foreign-currency debts should reduce foreign-exchange mismatches by using capital-flow management or macroprudential policies, in addition to debt management operations to smooth repayment profiles.

In addition to fundamentals, with financial markets tightening, some countries are seeing signs of market disruptions such as rising currency hedging premia and local currency financing premia. Severe disruptions in shallow currency markets would trigger large changes in these premia, potentially causing macroeconomic and financial instability.

In such cases, temporary foreign exchange intervention may be appropriate. This can also help prevent adverse financial amplification if a large depreciation increases financial stability risks, such as corporate defaults, due to mismatches. Finally, temporary intervention can also support monetary policy in the rare circumstances where a large exchange rate depreciation could de-anchor inflation expectations, and monetary policy alone cannot restore price stability.

For the United States, despite the global fallout from a strong dollar and tighter global financial conditions, monetary tightening remains the appropriate policy while US inflation remains so far above target. Not doing so would damage central bank credibility, de-anchor inflation expectations, and necessitate even more tightening later—and greater spillovers to the rest of the world.

That said, the Fed should keep in mind that large spillovers are likely to spill back into the US economy. In addition, as a global provider of the world’s safe asset, the US could reactivate currency swap lines to eligible countries, as it extended at the start of the pandemic, to provide an important safety valve in times of currency market stress. These would usefully complement dollar funding provided by the Fed’s standing Foreign and International Monetary Authorities Repo Facility.

The IMF will continue to work closely with our members to craft appropriate macroeconomic policies in these turbulent times, relying on our Integrated Policy Framework. Beyond precautionary financing facilities available for eligible countries, the IMF stands ready to extend our lending resources to member countries experiencing balance of payments problems.

Gita Gopinath, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas (IMF)

- Valeria, the amputee giving 1,000 other amputees new life - 25 April 2025

- Moses Baiden calls for unified African tech strategy - 25 April 2025

- Govt will settle debt owed Zoomlion-MPs - 25 April 2025