Ghana does not lack the capacity to build large-scale housing for its students and security services.

What it lacks, once again, is the political will to deliberately empower its own proven institutions.

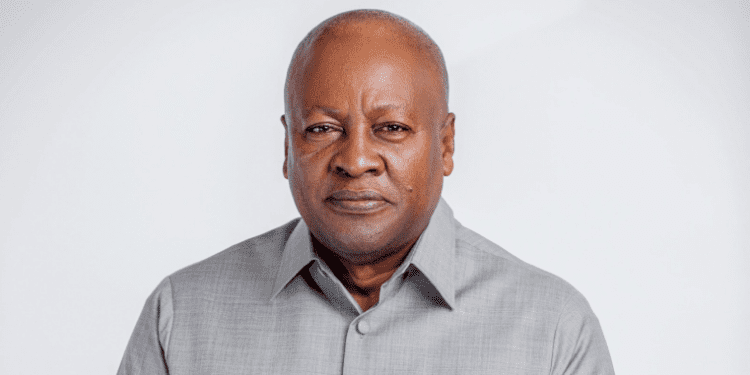

President John Dramani Mahama’s announcement of plans to construct a 10,000-bed student hostel at the University of Ghana and extensive housing for the security services using prefabricated technology should, by logic and national interest, have placed the 48 Engineer Regiment of the Ghana Armed Forces at the centre of execution—not a foreign company.

Yet the government has chosen to commission a Singaporean firm, reviving a familiar and troubling pattern: outsourcing strategic national infrastructure even when capable local capacity exists.

The Singapore deal and the outsourcing reflex

According to the President, the project stems from a bilateral agreement signed during a recent official visit to Singapore. Under the arrangement, a Singaporean company is to establish a prefabricated housing factory in Ghana, with machinery already shipped from Singapore and currently en route to Accra.

The company’s first assignment is the 10,000-bed University of Ghana hostel, with further mandates to construct housing units for the Ghana Police Service, Ghana Prisons Service, Ghana National Fire Service and the Ghana Armed Forces under the government’s “Big Push Agenda.”

In parallel, the Chief of the Defence Staff, Lieutenant General William Agyapong, has disclosed that government plans include more than 2,000 housing units across garrisons nationwide—about 700 in five garrisons in Accra alone—with projections of up to 8,000 additional units if all goes as planned.

On the surface, the ambition is laudable. Ghana’s student accommodation crisis is severe, and the housing challenges confronting security personnel are longstanding and urgent. But beneath the ambition lies a fundamental policy flaw.

A strategic omission with serious implications

The most glaring omission in the President’s announcement is the near-total absence of the 48 Engineer Regiment from the conversation.

This is not a ceremonial military unit. It is Ghana’s most experienced public engineering and construction firm, built precisely to execute complex infrastructure projects in the national interest.

To bypass the 48 Engineer Regiment in favour of a foreign contractor is not a neutral procurement decision.

It is a policy contradiction that undermines years of public investment in local capacity, skills and institutional development.

A record that speaks for itself

The 48 Engineer Regiment has, for decades, delivered critical national infrastructure across Ghana.

It has opened up remote and economically isolated areas through the construction of feeder roads and bridges, including strategic bridges at Jeffisi and Kassana in the Upper West Region under national security intervention programmes.

These were not symbolic projects; they were lifelines that connected communities to markets, schools and healthcare.

Under “Operation Roadstar,” the Regiment drilled and constructed boreholes nationwide, addressing water insecurity in underserved communities.

In sports and community infrastructure, it played a central role in constructing the El-Wak Sports Stadium and, more recently, built and commissioned the SAPPERS Sports Complex at its Teshie base, complete with an AstroTurf pitch, basketball court and volleyball arena.

Proven in crisis, relevant across generations

In moments of national crisis, the Regiment has consistently delivered.

It provided housing and bridging support during the devastating 1962 floods and played a vital role in the Akosombo Resettlement Programme in 1964. Its relevance has not faded with time.

In recent years, the Regiment has undertaken construction works at the University of Cape Coast to enhance campus security and safety—clear evidence that it can operate effectively within university environments similar to the University of Ghana.

Handling billion-Cedi projects with confidence

Perhaps most compelling is the Regiment’s leadership in high-value, technically demanding projects.

It is currently leading a GH₵6 billion national infrastructure project, including the 180-kilometre Awasutaka Bauxite Corridor.

This ranks among the most significant industrial infrastructure undertakings in Ghana’s recent history, involving extensive earthworks, logistics planning and engineering coordination.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the 48 Engineer Regiment was a key collaborator and supervisor in the construction of the 100-bed Ghana Infectious Disease Centre at the Ga East Municipal Hospital.

Delivered under intense time pressure and public scrutiny, the project succeeded through collaboration with the Ghana Institute of Architects, the Ghana Institution of Engineers and the Ghana Institution of Surveyors, all working pro bono.

That success remains a national demonstration of what empowered local expertise can achieve.

Why import what Ghana already has?

Given this record, it is difficult to justify why Ghana would commission a foreign company to build prefabricated housing for its own armed forces and security services without first positioning the 48 Engineer Regiment as the lead implementing institution.

If prefabricated technology is indeed the preferred solution, the rational national strategy would be clear: deliberately transfer that technology to the Regiment, equip it with the necessary machinery, and embed the capability permanently within Ghana’s defence and public works architecture.

Instead, the current approach risks repeating a familiar cycle—foreign firms arrive with turnkey solutions, execute contracts, repatriate profits, and leave behind limited local capacity.

Even when factories are established locally, ownership, intellectual property and strategic control often remain external. Ghana becomes a host, not a master, of the technology it relies on.

Housing for security services is a national security issue

This concern is even more pronounced because the beneficiaries of the housing are Ghana’s own security services. Accommodation for soldiers, police officers, prison officers and firefighters is not merely a welfare issue; it is a matter of national security and institutional stability.

Outsourcing such a core function while sidelining the military’s own engineering regiment sends an unsettling signal about trust, priorities and long-term planning.

Partnerships should build capacity, not replace it

This is not an argument against international partnerships. Foreign cooperation can be valuable, particularly where financing or specialised technology is required.

But partnerships must be structured to deliberately strengthen local institutions, not substitute for them.

Ghana cannot credibly preach industrialisation, skills development and self-reliance while defaulting to foreign execution for projects that local institutions are demonstrably capable of delivering.

The University of Ghana Hostel as a test case

The 10,000-bed University of Ghana hostel sharpens the issue. It is a significant undertaking, but well within the technical and logistical capacity of Ghanaian engineers, architects and builders—especially when coordinated through a disciplined, state-backed institution like the 48 Engineer Regiment.

Empowering the Regiment to deliver this project would not only address an accommodation crisis but also leave Ghana with an expanded, battle-tested public construction capacity for future national needs.

A defining development choice

At its core, this debate is about development philosophy.

Does Ghana intend to remain perpetually dependent on external actors for execution, or does it want to intentionally build strong national institutions capable of delivering complex projects repeatedly and sustainably?

President Mahama’s “Big Push Agenda” speaks to ambition and scale.

But a truly transformative big push must also be inward-looking.

It must ask not only what gets built, but who builds it, who learns from it, who retains the skills, and who controls the next generation of technology.

Building homes or building sovereignty

The 48 Engineer Regiment embodies decades of public investment in skills, discipline and institutional memory.

To bypass it in favour of a foreign company—especially for housing tied directly to national security and public education—is to weaken, rather than strengthen, Ghana’s development foundations.

If Ghana is serious about building a resilient and self-reliant economy, the path forward is clear.

Foreign expertise, where necessary, should be used to train, equip and elevate Ghanaian institutions—not replace them.

Empowering the 48 Engineer Regiment to lead national housing projects would not only deliver homes.

It would deliver capacity, confidence and sovereignty. That is the legacy a genuinely development-driven policy should seek to secure.