Ghana’s food insecurity remains widespread and sensitive to economic and seasonal shocks, with 12.5 million people affected in the third quarter of 2025, according to the Ghana Statistical Service.

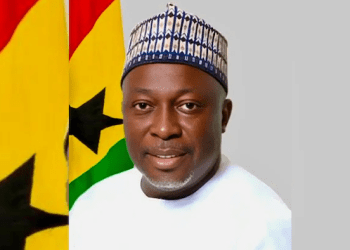

Government Statistician Professor Alhassan Iddrisu said the issue is a national development challenge.

“This release is important because food insecurity is not just a social issue,” he said. “It affects household welfare. It affects child health, labour productivity, business confidence and national development.”

“Our goal for this release is very simple, to provide clear, timely and credible evidence that helps stakeholders, including government, businesses, communities and development partners, make better decisions in the food security space,” he added.

The report shows food insecurity rising overall since early 2024, despite recent easing.

“This tells us something very important, that food insecurity in Ghana is volatile, and that it responds quickly to economic conditions, to seasonal patterns, as well as surprise movements,” Prof Iddrisu explained, adding that “despite the recent easing we have seen in food insecurity, the overall trend since the 2024 quarter one is upward, indicating rising vulnerability”.

“Just within one quarter, the number of food-insecure persons reduced by 900,723 persons from 13.4 million in quarter two to 12.5 million in quarter three,” he said.

However, he cautioned: “Given that in the third quarter of 2025 the number of people who are food insecure is 12.5 million people, that number is still very, very significant, and as a country, we have to do everything possible to ensure that that number is reduced to the very minimum.”

“This approach asks households eight simple questions about their experiences over the last three months,” Prof Iddrisu said. “These questions include, ‘Did you worry about having enough food? Did you eat less than you should have? Did you skip meals? And did anyone go a whole day without eating?’”

“From 2024 quarter one to 2025 quarter three, moderate food insecurity was consistently higher in female-headed households,” he said.

“This possibly reflects structural factors such as income differences between males and females, employment opportunities and also caregiving responsibilities,” he added.

“This tells us that food insecurity in Ghana is deeply spatial, not evenly spread,” he stressed.

“Nationally, about 53 per cent of households reported worrying about food in the third quarter of 2025,” he said. “The problem is more severe in rural areas… about 60 per cent compared to 48 per cent in urban areas.”

“Nationally, households with malnourished children recorded food insecurity rates of around 44 per cent,” he said.

“This is not just a food issue, it is a human capital issue with long-term implications for learning, productivity and health,” he warned.

“Food insecurity declined steadily as educational attainment increased,” he said. “Education matters a lot in addressing food insecurity issues,” he emphasised.

“Even when severe deprivation is relatively low, widespread moderate insecurity still affects daily life,” he cautioned.

“Although the number is modest, it represents deep structural vulnerability,” he added.

He concluded Ghana performs better than some regional peers — “If you compare this to our 38.1 per cent… I think Ghana is doing pretty well.” — but acknowledged lower rates in countries such as Egypt, South Africa and Brazil.